Journey to the Center of Infinity

So... are we there yet?

It is way bigger than you think

Think of the biggest number possible. Let me give you some help. A googolplex is the largest named number that is equal to 10 raised to the power of a googol (\(\text{googol} = 10^{100}\)).

Then there is Graham’s number, which was derived by Ronald Graham in the late 1970s. Graham’s number is connected to a problem in Ramsey theory, which is an area in mathematics that deals with combinatorial objects.

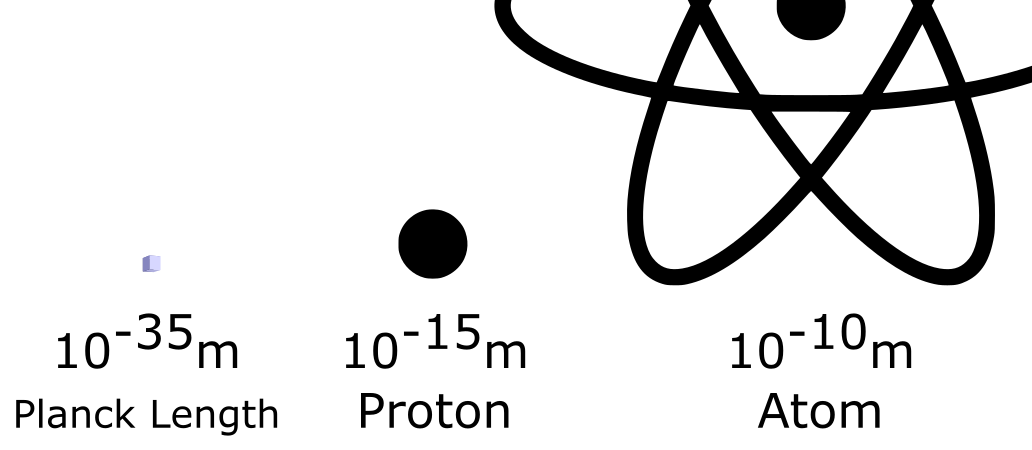

You might think that this doesn’t make much sense, but in the same way that one would instinctively know that an adult has to be taller than a baby, we can also intuitively define that this upper bound is much bigger than any other quantity. So large that there is no physical analogy that I can give you. If we were to pixelate the entire universe in the smallest possible size allowed in quantum physics, that would still only give us a mere \(10^{184}\).

Let’s take Graham’s number and see how much bigger we can go. We could simply have Graham’s number to the power of itself, but let’s just use an even more powerful tool. The hyper-operators. The Knuth arrow notation (\(\uparrow\)) might not be a symbol you are used to, but it can represent nested exponentiation concisely.

- The single arrow (\(\uparrow\)) represents exponentiation:

- Two arrows, one right after another, (\(\uparrow \uparrow\)) represents tetration:

- Three arrows (\(\uparrow\uparrow\uparrow\)) represent pentation. As much as I want to give you the final answer to this example… it’s just ridiculously big:

Although these hyper-operations can be powered up even further using the Conway chained arrow notation, this should suffice for now. Now let’s try applying this tool to the already ridiculously big Graham’s number. Consider using it as a base for the pentation and itself for the pentation exponent. And just for kicks, let’s just take the factorial

Even after defining an already impossibly large number and using an operator that skyrockets it to a power of itself, this is still microscopic when compared to infinity. Graham’s number goes beyond a number that would be possible in this universe, so it is quite a challenge to comprehend the vastness of infinity. Yet we use infinity constantly in mathematics. Its use dates back to the 4th century BC with Euclid’s fundamental work in geometry and is also the basis for the development of calculus by Newton and Leibniz around 350 years ago.

The Intuitionists against the Formalists

What later became known as the “Foundational Crisis of Mathematics”

Cantor is historically remembered for developing set theory, which is a branch of mathematics that studies collections of objects/numbers.

Natural numbers are a very simple set. These are always positive, whole numbers, and they do not include any fractions or decimals. Let’s take this set and put it in a box marked with the symbol \(\mathbb{N}\):

\[1\qquad 2\qquad 3\qquad 4\qquad 5\qquad 6\qquad \infty \rightarrow\] \[\downarrow\] \[\begin{CD} . @= . \\ @. @| @|\\ @. . @= . \end{CD}\] \[\qquad \quad \mathbb{N}\]Natural numbers are a subset of Real numbers, which also include fractions, irrational numbers, and so on. Let’s put this set on a fresh box marked with the symbol \(\mathbb{R}\):

\[\leftarrow -\infty\quad -3\quad -2\quad -1\quad -0.5\qquad 0\qquad 0.5\qquad 1\qquad 2\qquad 3\qquad \infty \rightarrow\] \[\downarrow\] \[\begin{CD} . @= . \\ @. @| @|\\ @. . @= . \end{CD}\] \[\qquad \quad \mathbb{R}\]Although both boxes contain an infinite amount of numbers, you could instinctively claim that there is more “stuff” in the box that has the real numbers. The set of real numbers includes natural numbers besides other sets, so the infinite number of things in one box must be bigger than the other:

\[\begin{CD} . @= .\\ @| @|\\ . @= .\\@. \vcenter{\hbox{$\displaystyle \mathrm{\mathbb{N}}$}} @. \end{CD} \qquad < \qquad \begin{CD} . @= .\\@| @|\\ . @= .\\@. \vcenter{\hbox{$\displaystyle \mathrm{\mathbb{R}}$}} @.\end{CD}\]That leads to a strange outcome that breaks any statement in the previous section. You can quantify infinity. It’s no longer an abstract tool like functions, combinatorics, or graphs. This outraged the formalists, who could not fathom considering infinity as anything else. But it was too late. As David Hilbert, a famous German mathematician piously puts it:

“No one shall expel us from the paradise that Cantor has created”

Indeed, the genie was out of the bottle and the nature of mathematics was put into question. What is the proper role of intuition in mathematical reasoning? Is mathematics truly objective or absolute? What is the nature of similar mathematical objects? These are philosophical questions, but these led to the advancement of computer science, model theory, and theoretical physics.

However, there is no satisfying end to this story. Both the intuitionists and formalists developed multiple solutions to the apparent paradox.

The questions that sparked this debate were not answered. But how could they? When mathematics itself says that they cannot be answered. In 1931, Kurt Gödel showed that any consistent axiomatic system that is powerful enough to encompass arithmetic must be incomplete.

Infinity in a physical world

While scientists have recently rejected philosophy towards a tendency for objective truth, the philosophical paradox of infinity can lead to some very interesting ideas. For over two thousand years, Zeno’s paradoxes have challenged our understanding of the physical world.

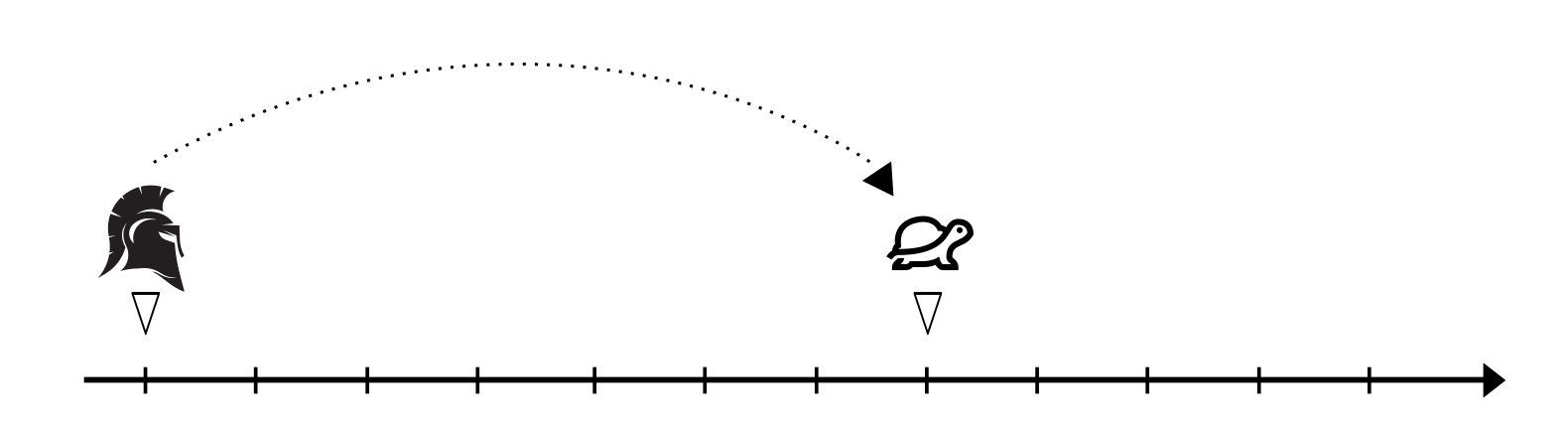

While traveling, Aristotle met the great Greek hero Achilles.

Achilles laughed at the poor pace that the tortoise had, and reached its last position in no time. He would beat the animal without breaking a sweat:

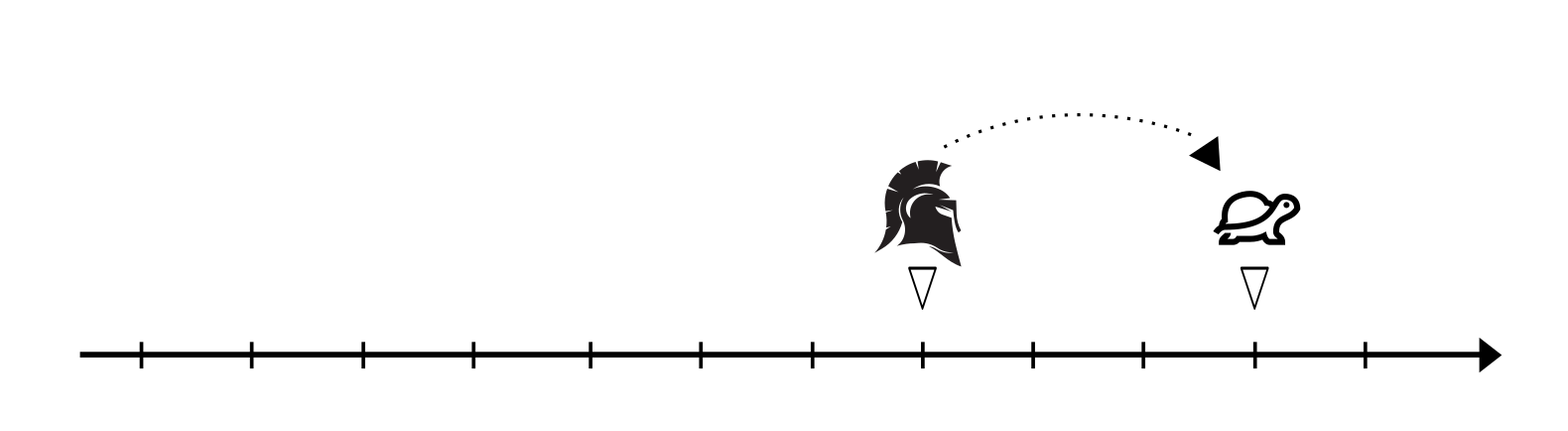

Noticing the apparent frustration of Achilles not being able to overtake the tortoise, Aristotle chimed in with the reminder of the challenge “You can only move to where the tortoise has already been”.

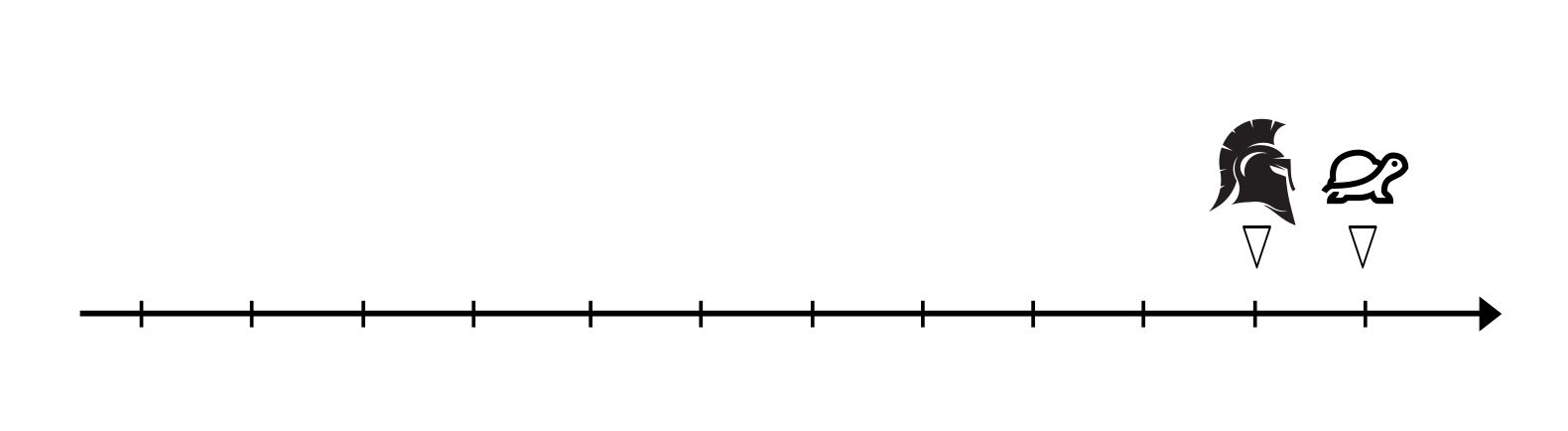

It was too late before Achilles understood the trick. There was no way that he would be able to get ahead of the turtle even if he was twice as fast as he is now. For this, Aristotle stated the obvious fact that was forgotten “In a race, the quickest runner can never overtake the slowest, since the pursuer must first reach the point whence the pursued started so that the slower must always hold a lead”.

While the tale might seem silly at first, it presents a questionable statement about reality. To stick to the rules, could Achilles travel an infinitely decreasing space to reach the tortoise’s last position? As British mathematician Bertrand Russell claimed, the paradox is “immeasurably subtle and profound”.

What about if we went in the other direction? As far as we know, there is no limit to how big an object can be

Even though they lead to paradoxical statements, both are considered to be true under relativity. It might seem counter-intuitive, but this is stemming from a challenge in scientific understanding. Multiple theories regarding the same phenomena can be correct under their own set of circumstances.

Yeah, we are not quite there yet

The paradox of infinity has challenged and inspired human understanding for thousands of years, from the ancient Greeks to modern scientists. It raises significant questions about the nature of space and time and challenges our understanding of the physical world. The pursuit of knowledge and understanding in mathematics and science has led to substantial developments and advancements. The existence of multiple theories and explanations for a phenomenon is not a weakness, but rather a strength that allows for continued exploration and discovery. As we continue to explore the mysteries of nature, the pursuit of knowledge in mathematics and physics will continue to be intertwined. This is because each field informs and inspires the other. As we think about the paradox of infinity, we are reminded of the beauty and complexity of the universe. We are also reminded of how endless the possibilities of discovery and exploration are. It illustrates the complex and contradictory nature of academia, where differing theories and ideas can contradict and work against each other. While this can be frustrating and challenging, it ultimately leads to a more dynamic and innovative environment for scientific inquiry. The pursuit of knowledge and understanding requires the willingness to challenge established beliefs and explore novel ideas, and this often involves engaging in rigorous debate and criticism. While we may never fully understand the true nature of infinity, the pursuit of knowledge and understanding continues to inspire us to push the limits of our understanding. This leads to discoveries and breakthroughs that benefit all of humanity.

“Science is not only compatible with spirituality; it is a profound source of spirituality. When we recognize our place in an immensity of light years and in the passage of ages, when we grasp the intricacy, beauty, and subtlety of life, then that soaring feeling, that sense of elation and humility combined, is surely spiritual.” - Carl Sagan