The Multiverse of Madness

The 4-levels of a Multiverse Theory

In another time. In another place

Have you ever wished you could go back in time and change a decision you made? Many of us have fantasized about how our lives could have been different if we had made different choices. What if we were working somewhere else? What if we were married to someone else? What if we lived in a different part of the world? While this is just our little fantasy, it’s something that many people think about.

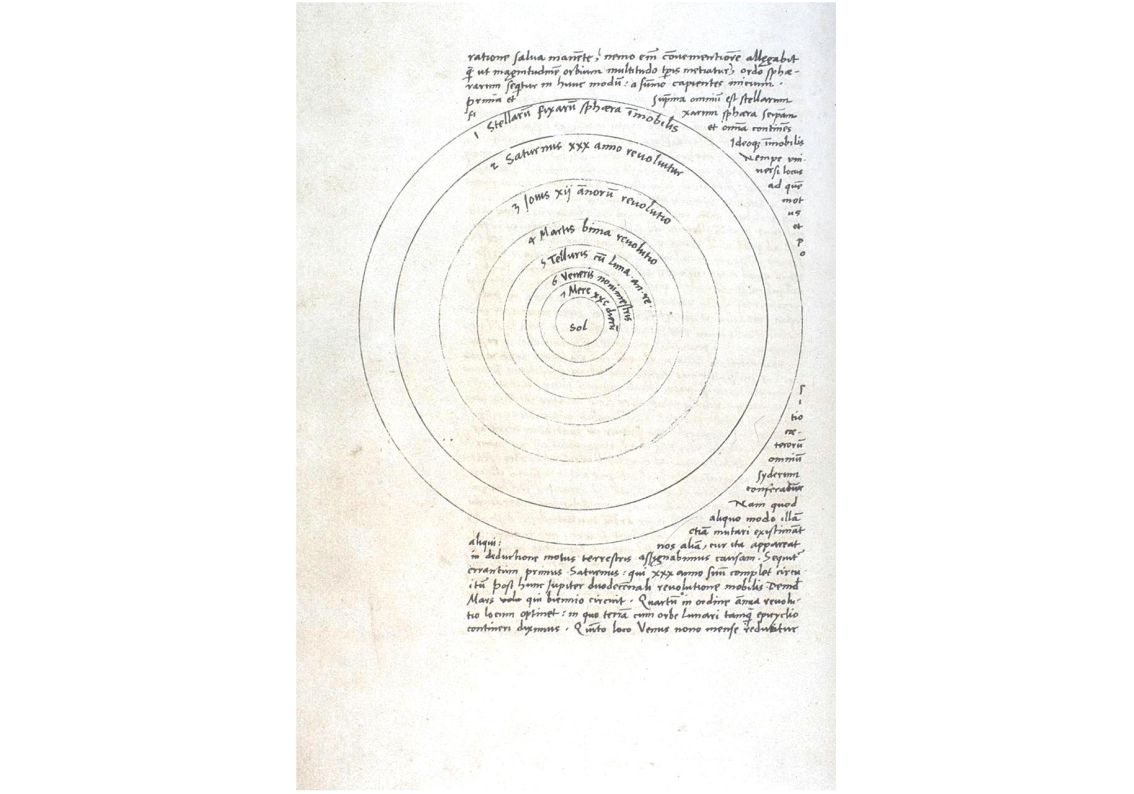

The idea of parallel universes dates back so far that it presents the idea that it was never exclusive to superhero movie sequels. It has been around for centuries and may have stemmed from humanity’s desire for exploration or a more ‘fantastic’ reality. Anaximander, a philosopher who lived in present-day Turkey in the 6th century BCE, proposed the existence of an infinite number of worlds.

A recent analysis has proposed that the idea of parallel universes is far from fiction, but that it also requires a proper definition of ‘parallelism’. Max Tegmark, a Swedish-American physicist and cosmologist, has proposed a framework for categorizing different levels of the multiverse.

Level I. An extension of our universe

The first level of the multiverse theory is a proper definition of Anaximander’s proposal. In an infinite universe, every possible configuration can be eventually reached. Although we have previously discussed the limitations of infinity in physics, our universe can technically be described as infinite.

At the macroscopic scale, we use statistical mechanics to categorize the behavior of large collections of particles as ensembles. This means that any configuration of position and velocity from the particles is equally likely.

However, energy cannot be created out of nothing.

In simpler terms, imagine being trapped in a room that is continuously expanding. The room has a considerable number of resources to ensure your survival, such as water and food. The room’s expansion is so fast that you would never see the walls of the room. Even if you had enough food and water to last you decades, it will eventually run out. This is the case within our observable universe. Even if it was endless, there’s a static quantity of ‘stuff’ inside of it.

Level II Different constants

Our universe requires a set of unchangeable values that define physics. These are much more fundamental that the radius of an atom or the acceleration of gravity. Many of the things that we call ‘constants’ are only applicable on Earth or are the subject of some broad approximation. \(9.8 \space \frac{m}{s^2}\) is a value that we assign to the acceleration that an object feels towards Earth. This value won’t serve us much if we were stranded on some anomalous planet or deep in the vacuum of space.

As far as we know, there are only three fundamental constants that are obeyed strictly throughout the universe:

- The maximum speed any object has an upper limit which is defined by the speed of light \(c = 299,792,458 \space \frac{m}{s}\)

- Objects attract each other with a force that is proportional to the product of each object’s mass and a gravitational constant. We call this the Gravitational’s constant \(G = 6.67430(15)×10^{−11} \frac{m^3}{kg⋅s^2}\)

- The uncertainties of an object’s position and momenta cannot be smaller than Planck’s constant \(h = 6.62607015 × 10^{-34} \frac{J}{Hz}\)

These limitations are supreme, and they have been since the birth of our universe. But consider the possibility that during the birth of our universe, these constants change ever so slightly.

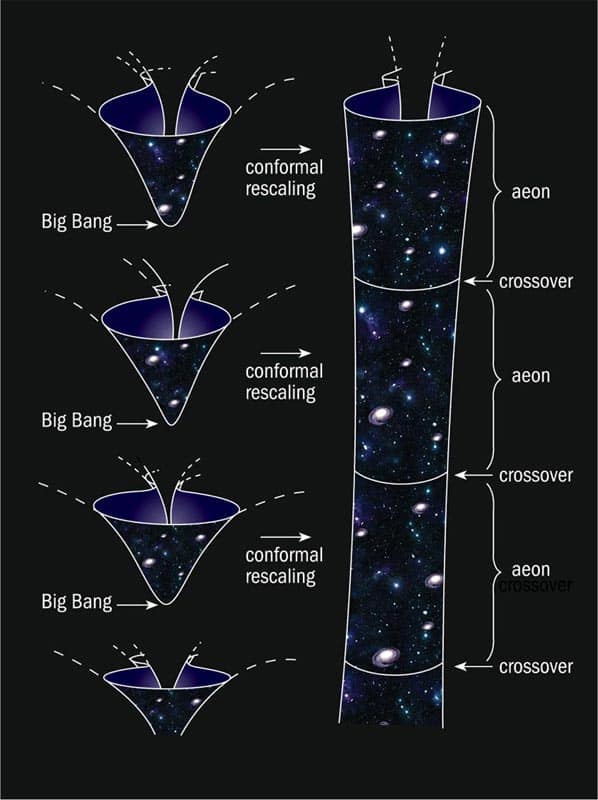

An alternative theory, which is much more controversial, presents our universe as cyclic.

During these ‘bounces’, the constants that define our current universe might change. Give rise to different types of matter and energy, allow for faster-than-light travel, or maybe even make space exploration impossible. In some variations matter and energy might be impossible, creating a completely void universe.

Again, we end up falling back to the same problem in our Level 1 universe. Arguments that encourage the theory of a bouncing universe tend to ignore or diminish the impact of entropy.

There have been some reasonable attempts to justify this theory. You have to remember; we are merely at the second ‘most likely’ level of the multiverse theory. This allows theories to rely on the least amount of assumptions to provide necessary explanations. Proponents of a cyclic universe have included Albert Einstein,

For most people, the idea of a cyclic universe is logical. We live in a world of cycles. Much of the study of Biology and Geology is made up of cyclic processes where every component is re-utilized. The problem lies with the fact that these are not perfectly conserved cycles. These have the unquestionable consequence of a rising entropy, or rather, the decrease of usable reacting components. At some point in these cycles, a perishable resource has to be expended for these cycles to continue undisturbed. This gives the impression that these cycles are endless. On the time scale of millions of years resources such as water, geothermal, and solar activity are finite.

Level III The Many-Worlds Interpretation

In quantum mechanics the nature of probabilistic events implies that if something is allowed, it may happen, it can happen, and it will happen.

The ‘Copenhagen interpretation’ is the most widely accepted explanation of probabilistic events in quantum mechanics.

One of the alternative theories regarding this behavior is the ‘Many-Worlds interpretation’ from Hugh Everett III.

These parallel instances would also have the capacity to obey different physical constants. Instead of being subjected to the theory of a cyclic universe, the multiple worlds interpretation relies on an alternative view of a proven quantum physics phenomenon.

However, the many-worlds interpretation is considered untestable and therefore unscientific.

“The most outrageous explanation, even if it is the only one, cannot be possibly true.”

Level IV Ultimate Ensemble

The final level of Tegmark’s categorical multiverse is called the ‘ultimate’ ensemble. As stated before, each level rejects a known constraint of our standard universe. At the end of the multiverse hierarchy, we find ourselves with a multiverse that follows nothing but the laws of mathematics.

However, doesn’t our universe already follow the laws of mathematics? Certainly, but not all of them. Some mathematical concepts, such as imaginary and transfinite numbers, have no physical representation. While they can be used to represent many physical properties, they are not used to represent real quantities.

Let’s make a general assumption here:

Physics must obey mathematics, but mathematics does not encompass all of physics.

In this ultimate ensemble, every mathematically possible structure is conceivable in a different universe. This also encompasses all previous levels and expands on the level II multiverse theory of different physical constants. This implies that not only different values for gravity and the speed of light but also different mathematical equations could exist. In our universe, the location of an object is defined by three positional values (such as length, height, and depth) and the time at that position. Other universes might ignore that and require any number of spatial and time dimensions, or perhaps none at all.

Such a reality could provide relevance to theories that have a consistent mathematical basis but cannot be accepted in our world. Quantum mechanics represents the physics of small objects very well while struggling with the physics of large objects. Conversely, relativity is successful in explaining the physics of large objects but struggles with small objects. Although both fields have had success, there is still no way to reconcile them into a single theory, known as the “theory of everything.”

String theory was developed as an attempt to successfully combine the theories of quantum mechanics and relativity by describing fundamental particles as tiny, one-dimensional strings. The level II multiverse is consistent with string theory in which our universe is just one of many possible universes with different physical laws and constants. However, some versions of string theory propose that there could be additional, higher-dimensional objects called “superstrings” that would be acceptable at this level.

Although some critics argue that string theory is a waste of time and resources, the potential consequences of an “Ultimate Ensemble” multiverse are considerable. String theory has been proven to be mathematically consistent. If there is a universe that respects string theory and can be correctly addressed as ‘the theory of everything’ of some universe then perhaps it could be translated to our own. If the theory works in one universe, it may be possible to adapt it to ours with some effort.

There’s no place like home

Why are there so many songs about rainbows

And what’s on the other side?

Rainbows are visions, but only illusions

And rainbows have nothing to hide - The Frog, Kermit

There might be a world on the other side of the rainbow that is better than ours. Limitless energy, endless nourishment, absent of conflict. It can inspire a symbol of hope and possibility. These theories might serve as a reminder that our imagination and aspirations have the power to transcend the limitations of our present circumstances. Perhaps the desire for such a world stems from the disheartening reality of our current one.

The pursuit of hypothetical realities could be seen as a distraction from the responsibilities and challenges that we face in our current world. String theory has been long criticized for consuming a significant amount of resources and funding without providing concrete results or practical applications.

We could draw strength and inspiration from the vision of different worlds while remaining grounded in the reality of our current. I consider the pursuit of ideas such as string theory as an essential part of scientific discovery and progress. The basis of highly influential theories such as relativity was born from such research that was considered ‘impractical and baseless’. At the same time, we could harness the inspiration and hope that the notion of an alternate world provides to motivate us to work towards creating a better reality for ourselves and those around us.